Formula 1 epitomises the fusion of sport, technology, and global commerce, ever since its formation in 1950. It is a high-speed ecosystem where engineering excellence meets strategic financial management. Beyond its spectacle of speed and competition, F1 operates as a billion-dollar enterprise, interlinking innovation, logistics, marketing, and data-driven decision-making to sustain its absolute dominance in the modern entertainment economy.

Twenty of the fastest drivers in the world, filled with money, fame, and glory. Formula 1 has been and will continue to be one of the most technologically advanced and financially complex sports on the planet. Underneath the glamour of Grand Prix weekends lies a complex, intricate business model in which constructors operate as both high-performance engineering innovators and global marketing ambassadors (Formula 1 Miami, 2024). A team’s success is not only based on its speed on the track but also on its overall finance, logistics, and strategy.

Figure 1: The safety car boarding the DHL plane. Source: NYT

Team operations and logistics form the backbone of the Formula 1 ecosystem. Each season, teams travel across five continents, 24 cities in 21 countries. Teams transport more than 1,000 tonnes of equipment over the season, including race cars and spare parts, hospitality units, and data servers for each race (Haldenby, 2019). The complex logistics network coordinated by Formula 1 Management and its freight partner, DHL, must operate consistently, down to the minutest detail, to ensure there are no delays to any team’s performance. Drawing a parallel to the Sunday race, where the margin of error is extremely thin, the back-to-back races allow only three days to deconstruct, transport, and construct everything a team needs for its competitive edge (Haldenby, 2019). If a team intends to trial new components, these parts usually travel alongside team members, often checked in as oversized luggage at the team’s departure terminal. Meanwhile, Pirelli, Formula 1’s official tyre provider, will operate dedicated aircraft to deliver all race tyres, and Formula 1 itself manages the transport of around 150 trackside cameras and extensive cabling required to broadcast live footage from each circuit (Formula 1 Miami, 2024).

Revenue generation is equally critical. Teams earn income primarily through four channels: Formula 1’s commercial revenue distribution, corporate sponsorships, technical partnerships, and merchandise sales (Liberty Media Corporation, 2025). While Formula 1 itself earns income from sponsorship, race promotion fees, media rights, and merchandise. Host cities for races develop a mutually beneficial relationship with Formula 1 itself. Global event promoters pay substantial fees to secure the right to host a prestigious Grand Prix weekend. In return, the city receives a boost in tourism, domestic economic stimulation, and international exposure. Race promotion fees, paid by global event organisers, provide a stable and gradually escalating income stream, accounting for 29.3% of total revenue (Phelan, 2025). While the largest single source of income, media rights, accounts for 32.8% and is fuelled by premium broadcast deals and rapid digital growth.

It is no surprise that F1 drivers earn some of the highest athlete salaries in the world, given the significant physical risks of the sport. Driver earnings are not part of the F1 budget cap, so teams are free to pay their drivers as much as possible. Superstars’ base earnings range from around $45 million for Max Verstappen to $55 million for Lewis Hamilton (Forbes, 2024). Beyond this, drivers also earn hefty incomes through personal sponsorships, livery deals and social media. However, not every driver reaches Formula 1 purely through talent or equal financial opportunity.

Figure 2: Grid Ironmen: Max Verstappen and Lewis Hamilton are F1’s two top earners for the third straight year. Source: Forbes

The term “pay driver” refers to drivers who secure external funding from family wealth or personal sponsors in exchange for a seat (Autosport, 2024). While this is often viewed critically, it can sometimes be important for teams with limited budgets, as it provides millions in financial support. On the other hand, drivers without financial backing usually rely on junior development programs or manufacturer academies to advance. This can mean years of performance-based selection and uncertain contracts. The following case study of this contrast can be seen between two drivers who reached F1 through entirely different financial paths, Lance Stroll and Esteban Ocon.

Lance Stroll, currently racing for Aston Martin, made a prominent debut by securing a podium in a Williams in 2017. His father, billionaire businessman Lawrence Stroll, owns the Aston Martin F1 team, which has forced him to prove his worth constantly, as every good or bad performance from him is looked at quite closely by fans and the media, who often question whether his place in Formula 1 comes from talent or family influence. Regardless, he has a lot of experience in motorsport, having dominated the Italian F4 Championship in 2014, won the Toyota Racing Series in 2016 and also claimed the FIA European Formula 3 title (Total Motorsport, 2025).

Figure 3: Estaban Ocon and Lance Stroll. Source: X

Esteban Ocon, currently racing for Alpine, joined Renault’s driver development programme at just 14, and went on to win the FIA Formula 3 European Championship as a rookie in 2014, followed by the GP3 Series Championship in 2015. Unlike other drivers on the grid, however, he came from a working-class background. His parents sold their home and automobile repair shop and lived in a caravan to support his F1 career (Autosport, 2024). His strong performances caught the attention of Mercedes, which signed him to its junior driver programme. This helped him secure his first F1 seat at Manor in 2016, before moving to Force India and later Renault (now Alpine) (Total Motorsport, 2025).

Upon entering the 21st century, with F1 over five decades old, it soon became clear that a change in marketing was needed to keep it relevant and attract the new generation raised in a digitalised world. By 2015, surveys clearly indicated that F1 was headed in the wrong direction. Fans expressed concerns that the sport was alienating them due to a perceived disproportionate focus on business interests, and heavily encouraged stronger engagement with the drivers (Taylor, 2015). F1 began developing an image and reach problem, where a lack of a direct relationship with fans severely damaged retention, due to a failure to commit to digital marketing and communications fully. It was ironic that one of the most technologically advanced sports in the world was refusing to adopt the practices of a digital world (Misra, 2021).

Figure 4: Live statistics and tracking of all drivers during an F1 race. Source: Formula 1

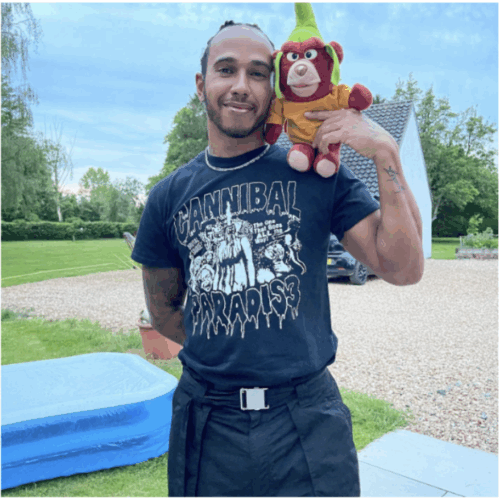

In response to such issues, F1 brought in Liberty Media to take over commercial operations in 2017. Leveraging the vast amount of data F1 holds, they immediately sought to produce off-track stories and generate fan engagement. Whilst the data was previously used only by teams to improve their cars and strategies, fans can now also use it to understand races better, analyse strategies, compare competitors, and observe performance statistics, providing a much wider range of content to consume (Misra, 2021). Through this, fans can also become more educated, which is incredibly encouraging for retention. Meanwhile, to specifically target younger fans and build a stronger digital presence, social media activity increased significantly. Notably, this includes opening access to drivers, who were previously barred from having any significant online presence or even interacting with fans outside approved venues. Now, being able to see into their lives through sites like Instagram allows fans to feel more connected to their favourite drivers, seeing them as real humans instead of just rich people driving fast cars (Misra, 2021). Furthermore, F1’s new 2019 Netflix series, Drive to Survive, demonstrates its ability to adapt to the evolving ways new generations consume content. Offering a unique perspective of the sport by showcasing a more personal side of the drivers, the show serves as another key tool to keep fans engaged and help them relate (Business Models Inc, 2025).

Figure 5: F1 drivers (Lewis Hamilton above) become more humanised with social media. Source: Instagram

Overall, Liberty Media’s marketing turnaround has achieved an unprecedented increase in global audience engagement, especially among youth. F1 now boasts 500 million fans, of which a third comprises the new generation, having joined the sport’s following following the sport’s shift towards audience engagement through a strong digital presence (Business Models Inc, 2025). From this, it is clear that F1, much like other sports, requires a dynamic marketing strategy that consistently adapts to a world rapidly evolving in tastes and technology, where shifts in focus must be made regularly to accommodate each new generation.

Figure 4: Drive to Survive. Source: The Conversation

Formula 1 is a high-speed business, powered by global logistics and supported by diverse partnerships and revenue streams. Drivers come from different backgrounds, some being more fortunate than others. With Liberty Media’s takeover and Netflix’s Drive to Survive Show, F1 is now more humanised, with more interactions with the audience, and has strengthened itself as an entertainment economy.

Amazing Cars and Drives. (2025, June 17). Lance Stroll: Formula 1 journey beyond the headlines. Amazing Cars and Drives. Retrieved October 21, 2025, from https://amazingcarsanddrives.com/lance-stroll-formula-1-journey/

Autosport. (2024, October 13). The tough times that led to Ocon’s F1 career. Autosport. Retrieved October 21, 2025, from https://www.autosport.com/f1/news/tough-times-that-led-to-ocons-f1-career/10767220/

Bhambwani, R. N. (2023). The Evolution of Formula 1: From Racing Passion to Global Business Powerhouse. Retrieved from https://medium.com/formula-one-forever/the-evolution-of-formula-1-from-racing-passion-to-global-business-powerhouse-fe20dd33c1ae

Business Models Inc. (2025). The Business Model of Formula 1. Retrieved from https://www.businessmodelsinc.com/en/inspiration/blogs/the-business-model-of-formula-1

Forbes Australia. (2024, December 11). Formula 1: Highest-paid drivers of 2024. Forbes Australia. Retrieved October 21, 2025, from https://www.forbes.com.au/news/sport/formula-1s-highest-paid-drivers-2024/

Formula 1. (n.d.). Esteban Ocon – F1 driver for Alpine. Formula 1. Retrieved October 21, 2025, from https://www.formula1.com/en/drivers/esteban-ocon

Formula 1 Miami. (2024, February 8). The Logistics of Formula 1. Formula 1 Crypto.com Miami Grand Prix. https://f1miamigp.com/news/press-release/the-logistics-of-formula-1/?srsltid=AfmBOopAGjpUWz6Df3Z0z3bP1dZzCrJLHtt37u5Kpqs-SrLaHh6KnA2Q

Haldenby, N. (2019, January 28). The Logistics Of Formula 1. F1Destinations.com. https://f1destinations.com/the-logistics-of-formula-1/

Liberty Media Corporation. (2025, February 27). Liberty Media Corporation. Liberty Media Corporation. https://www.libertymedia.com/investors/news-events/press-releases/detail/557/liberty-media-corporation-reports-fourth-quarter-and-year

Misra, A. (2021). Marketing Strategy that Revived the Fate of Formula 1. Retrieved from https://thestrategystory.com/2021/07/19/formula-one-marketing-strategy/

Motorsport.com. (n.d.). Esteban Ocon profile – Bio, news, high-res photos & high-quality videos. Motorsport.com. Retrieved October 21, 2025, from https://www.motorsport.com/driver/esteban-ocon/19624/

Motorsport.com. (n.d.). Lance Stroll profile – Bio, news, high-res photos & high-quality videos. Motorsport.com. Retrieved October 21, 2025, from https://www.motorsport.com/driver/lance-stroll/20950/

Phelan, M. (2025, March 17). How Does F1 Make Money? Inside F1’s Billion-Dollar Business Model. F1 History. https://www.formulaonehistory.com/how-f1-makes-money/

PlanetF1. (2024, May 16). Highest paid athletes in 2024: Forbes’ list reveals huge Max Verstappen and Lewis Hamilton fortunes. PlanetF1. Retrieved October 21, 2025, from https://www.planetf1.com/news/max-verstappen-lewis-hamilton-fortunes-forbes-highest-paid-athletes-2024

PlanetF1. (2024, October 10). F1 driver net worth 2024: The 10 richest drivers on the F1 grid. PlanetF1. Retrieved October 21, 2025, from https://www.planetf1.com/news/f1-driver-net-worth-2024-10-richest-drivers

Taylor, M. (2015). Formula 1 2015: Grand Prix Drivers Association releases findings from Global Fan Survey. Retrieved from https://www.foxsports.com.au/motorsport/formula-one/formula-1-2015-grand-prix-drivers-association-releases-findings-from-global-fan-survey/news-story/6eb687f34d04125dc655d8f4da4f78a2

Total Motorsport. (2025, June 17). Esteban Ocon – F1 driver profile. Total Motorsport. Retrieved October 21, 2025, from https://www.total-motorsport.com/f1-drivers/esteban-ocon/

Total Motorsport. (2025, June 17). Lance Stroll – F1 driver profile & biography. Total Motorsport. Retrieved October 21, 2025, from https://www.total-motorsport.com/f1-drivers/lance-stroll/

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.