Tariffs are one of the oldest instruments of economic policy, yet they remain among the most contentious. From Roman levies on silk to Trump’s trade wars, governments have used tariffs to extract revenue, protect domestic industries, and project geopolitical strength. Economists, however, warn that the hidden costs, distorted markets, higher consumer prices, and deadweight losses can outweigh the gains. This essay examines tariffs through three lenses: their historical evolution, their economic mechanics, and their modern deployment. In doing so, it assesses whether tariffs still work in today’s interconnected world.

Tariffs have been one of the oldest instruments of economic policy, dating back to ancient times. Early traders, such as the Roman Empire, had developed tariffs on silk and spices, with internal trade within Rome’s provinces taxed at rates of around 1-5%, while luxury goods entering from Asia or other external regions faced significantly higher rates (often 12-25%).

Fast forward to the 16th and early 18th century, the concept of mercantilism was embraced, where European nations aimed to maximise their exports, while limiting their imports to increase their wealth and power. One notable example is Britain’s Sugar Act of 1764, which raised duties on foreign refined sugar and molasses imported by the colonies, thereby granting West Indies growers a monopoly on the colonial market.

Figure 1: Tariffs in the 1800s. Source: Britannica

In the late 18th and 19th centuries, debates and shifts in tariff policy occurred, with variations across different countries. The first major law of the US Congress was the Tariff Act of 1789, with the primary goal of raising revenue for the new federal government. Meanwhile, in Britain, the tariff policy continued with mercantilist-style tariffs.

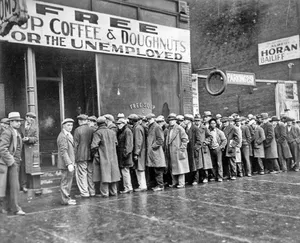

In the period leading up to World War I, tariffs remained relatively high, with the US maintaining rates at around 40%, and many new nations using these high tariffs for protection. The Great Depression of the 1930s marked the lowest point of international trade relations, as nations worldwide drastically increased their tariffs as a way of protection. The infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 in the US raised US import duties to record levels on over 10,000 products, exacerbating the already poor global economy.

Figure 2: Great Depression in the US. Source: Britannica

The aftermath of World War II led to a global reorientation of tariff policy. Twenty-three nations signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), with the average tariff reducing to 22% in the 1940s and below 5% in the 1990s.

In the 2000s, global supply chains and free trade agreements flourished; however, some countries have periodically resorted to tariffs as a policy tool for economic or strategic reasons. In the late 2010s, Donald Trump raised tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars of imports, targeting steel, aluminium, and especially Chinese goods. China responded with its own tariffs.

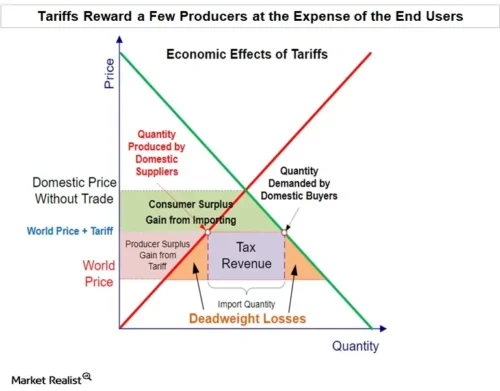

Tariffs are taxes imposed on imports of goods and services from other countries. They manipulate the supply and demand in domestic and foreign economies to reduce competition and protect domestic producers, raise revenue generated or are employed as a tool to exert political leverage. As the prices of foreign goods increase, the demand for local goods also increases, boosting domestic production and thereby increasing demand (Producer surplus gain). Meanwhile, the exporting economies face a negative demand shock, which causes lower sales (Consumer surplus loss). However, tariffs can also cause domestic economies to reduce efficiency and lead to high levels of inflation, which hurts consumers. This results in deadweight losses, which occur when a portion of welfare is not accessible to either consumers or producers, leading to an overall net welfare loss. The impact would depend on how much a firm depends on exports for production and the price elasticity of demand and supply. While optimal tariffs could theoretically be possible for a large economy with significant market power to improve its terms of trade, it is highly unrealistic.

Figure 3: Economic Effects of Tariffs. Source: Market Realist

Figure 3: Economic Effects of Tariffs. Source: Market Realist

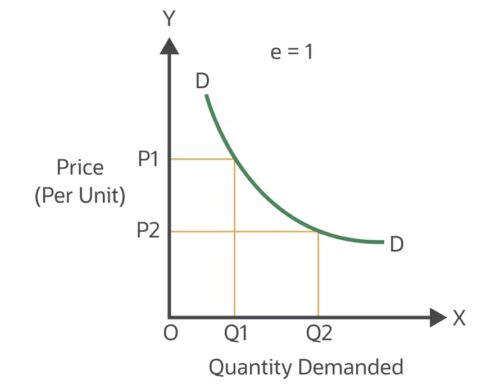

Figure 4: Unitary Elastic Demand. Source: NetSuite

Tariffs can have unintended impacts on global trade. Firms facing high costs due to tariffs may pass them on to consumers, which causes further price hikes. They can also cause inefficient resource allocation, where countries prioritise production in less efficient domestic industries rather than areas where it has a comparative advantage. This can have a detrimental effect, reducing productivity and hindering long-term growth. If domestic demand is inelastic, consumers continue to buy the same amount of goods and services regardless of price changes, so they bear a greater share of the cost while producers gain a surplus. If demand is elastic, however, the burden shifts to producers, who face reduced sales and revenue. Ultimately, these mechanisms and behavioural responses highlight the necessary trade-offs policymakers have to consider when trying to protect industries.

When we think about tariffs today, there is no doubt one world leader that immediately jumps into everyone’s head. Since taking office in January, US President Donald Trump has enacted sweeping tariffs on nearly all of America’s trading partners, regardless of their geopolitical relationship with the US, with a baseline rate of 10%. However, we must ask: Do these tariffs make economic sense? On ‘Liberation Day’, Trump described them as reciprocal, equal to half the rate of tariffs and non-tariff trade barriers imposed by other countries on the US.

Figure 5: Trump on his tariffs hearing. Source: NY Times

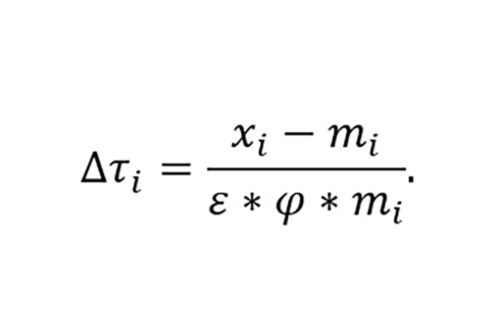

Alongside this, the Office of the United States Trade Representative also published a formula that the government had devised to calculate the appropriate tariff rate for each of America’s trading partners. However, economists have quickly identified an alarming error within the formula that inflates the tariffs and barriers assumed to be levied by foreign countries by four times. As a result, such reciprocal tariffs calculated through the formula are also highly inflated.

Figure 5: Trump’s tariff formula. Source: Bloomberg

Figure 5: Trump’s tariff formula. Source: Bloomberg

Although the justification for such tariffs is inherently economic, with Trump citing unfair trade practices of other nations and massive US trade deficits, the tariffs levied by Trump today appear increasingly disconnected from these economic justifications. Instead, the current administration uses tariffs as almost a diplomatic weapon, raising rates on countries as a form of punishment. One glaring example is that of India, where current US tariffs are at 50% for all Indian goods, particularly for Indian purchases of Russian oil. The effectiveness of using tariffs in such a way is yet to be determined, however, as it appears that the US has simply pushed India deeper into the arms of Russia and China, as seen by Indian Prime Minister Modi’s recent participation alongside Russian President Putin at China’s Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit, this being Modi’s first visit to China in 7 years. For Australia, it would appear necessary that our current government navigate around any actions that can potentially be viewed as opposing US interests, or risk facing a similar tariff.

Tariffs have travelled a long road, from the blunt mercantilist taxes of early empires to the sophisticated, yet politically charged, instruments of the 21st century. While they remain useful as levers of state power, the economic evidence is clear: tariffs inevitably impose efficiency losses, distort global supply chains, and often fail to achieve their stated goals. As the Trump era demonstrates, tariffs are as much about politics as they are about economics. For policymakers, the challenge is not simply whether to impose tariffs, but whether the short-term gains justify the long-term costs.

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.