Introduction: The Walking Debt

Around the world, countries are starting to see a rise in the number of zombie firms, which are firms whose earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) are less than their interest expenses for at least two out of three consecutive years—in short, their business cash flows cannot cover their debt. They are fundamentally unviable and do not contribute to economic growth but still exist—simultaneously dead and alive—much like the zombies of Hollywood fiction.

Policymakers have been paying more attention to the spread of zombie firms due to their effect on the economy. Although these firms pay higher interest rates to banks, they are unable to compensate for their default risk—effectively being subsidised by these banks. Though definitions vary, the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) defines zombie firms as follows:

According to Kearney, the percentage of market share taken up by zombie firms continues to increase. In 2023, it was estimated that there were around 2,370 zombie firms worldwide.

Figure 1. AMC has commonly been cited as an example of a zombie firm. Source: RCBJ

The mysterious world of zombie firms is often understated in discourse, but, in reality, entire sectors are supported by their existence. To understand them, we must first look at Japan’s Lost Decades.

Patient Zero: Japan’s Lost Decades

The end of the Second World War left Japan a poor and devastated nation. Nonetheless, extremely low interest rates, astute industry policy, a large and competent labour force, among many other factors, created a booming economy that would become Asia’s brightest—and richest—star. What has been dubbed as the “Japanese Economic Miracle” grew so potent it caused a fear among Americans that it would allow Japan to usurp American hegemony.

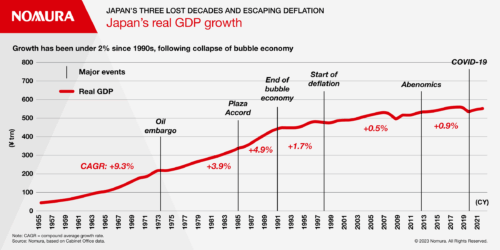

These fears were apparently unfounded as, in the 1980s, assets in Japan experienced a sharp decline in prices, wiping out savings. This effectively counteracted the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) aggressive monetary policy of cheap loans. The subsequent slowdown in gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate still leaves lasting economic and social challenges modern Japan grapples with. It was in this period, known as the “Lost Decades,” when the term “zombie firm” was coined.

Figure 2. Slowdown in Japan’s Real GDP Growth. Source: Nomura

The BOJ’s monetary policy is key to understanding the rise of zombie firms in Japan. To once again stimulate economic growth, the BOJ has slashed interest rates, even offering negative interest rates. This policy failed to stimulate the economy due in part to zombie firms that took advantage of these low interest rates to maintain their unproductive operations.

The persistence of zombie firms was caused by support from banks, which resulted in the proliferation of old dinosaurs that are not replaced by more efficient and innovative firms. By extension, these firms congested the market, draining capital and labour while hindering an already burdened Japanese economy.

Stopping the Spread: Financial Discipline Post-GFC

From 2007 to 2009, housing prices across America started falling, causing several significant banks, which had taken excessive risk, to collapse. Responses to the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) generally varied depending on how it affected different countries, but they often involved increased financial regulation.

Following the GFC, central banks rapidly decreased interest rates while purchasing large amounts of financial securities to increase economic growth. While these policies were important in ensuring that the crisis stabilised, they created conditions that were ripe for the zombification of firms. Governments’ support for certain industries following the GFC has also been criticised for propping up firms that are unproductive towards the economy.

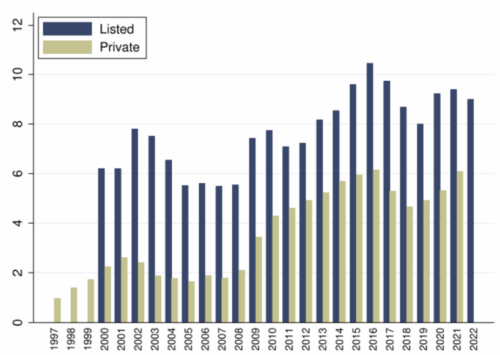

Figure 3. Share of zombie firms among listed and private firms. Source: Albuquerque and Iyer

In a study about the link between low interest rates and zombie firms, Ivana Blažková and Gabriela Chmelíková analyse trends in Germany and Czechia post-GFC. Both countries had divergent monetary policies, with Germany loosening its monetary policy initially. This led to an increase in zombie firms. In comparison, Czechia maintained higher interest rates, which slowed the increase of zombie firms at the cost of economic growth.

It should be noted that Germany has more robust financial institutions, which allowed them to reverse the trend of zombie firms. As such, zombie firms can be understood not just through the trade-off between long-term economic resource allocation and short-term growth, but also through the institutional mechanisms present in different countries.

Laying Zombie Firms to Rest

Zombie firms represent a fundamentally simple problem: with enough cash flows to cover only interest payments, they do not go bankrupt. This is exacerbated by low interest rates, continued support from banks and government support for unproductive firms. Possible, but difficult, solutions range from tackling low interest rates to better financial and accounting policing.

In 2023, as the Fed increased interest rates, hundreds of zombie firms filed for bankruptcy. The issue of zombie firms returned to national headlines as COVID-19 stimulus packages propped up several unproductive firms.

While this policy aims to create more efficient resource allocation within the market, the misallocation that gives rise to zombie firms keeps employment at a stable level. If interest rates were to rise, jobs would suffer. For those whose livelihoods rely on these firms, such a move would be politically unpopular. In European countries, for example, zombie firms account for 5-7% of employment. Any decisions by the ECB could increase euroscepticism.

As creative destruction increases, though, job search and retraining programs can be used to manage the social costs of bankrupt zombie firms. Insolvency reforms can help reduce barriers to corporate restructuring to resurrect zombie firms with less social costs. Furthermore, banking regulations can reduce the tendency for weak banks to bet on zombie firms.

It is also important to remember that shadow banks and private lenders are important pipelines for zombies to receive funding. These institutions, lacking transparency, increase systematic risk and have been referred to as “monkey business” by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Any policymaker must consider the influence these institutions have when targeting zombie firms.

Conclusion: Zombies in Australia

Zombie firms impact Australia’s economy in many tangible ways. KPMG Australia reports that the number of ASX-listed zombie firms has grown from 94 to 122 over 2024—an alarming 30 percent increase. As more government-supported small and medium enterprises (SMEs) suffer from poor cash flows, they have become another source of zombie firms. Low interest rates following the COVID-19 pandemic and a “light touch approach” to unviable firms from the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) have helped zombie firms remain solvent.

It is easy to root for the bankruptcy of these firms if one does not consider the human cost of ending zombie firms. Through its continued support for these firms, the Australian government has shown that it is focused on stemming unemployment rather than the long-term issues zombie firms bring. As the dead continue to rise, Australia needs to consider the moral weight of sustaining these firms and the drag they place on productivity and innovation.

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.