As economists and policymakers become more confident in the resilience of the US economy after the most aggressive tightening cycle in decades, the term “soft landing” has become more prevalent in public discourse. The term has become ubiquitous in contemporary monetary policy discussions, but it begs several questions: “What is a soft landing?” “How has it been achieved in the past?” and “Are we currently sticking to the landing?”

Economists such as former Federal Reserve vice-chair Alan Blinder have defined the phrase as “if GDP declines by less than 1%, or the NBER (National Bureau of Economic Research) doesn’t declare a recession after at least a year of a Fed rate-hiking cycle, that constitutes a soft landing” The term gained prominence in the 1970s when Treasury Secretary George Shultz used it to describe a scenario in which a mild economic cooldown could combat inflation without leading to a severe downturn.

Central bankers continue to grapple with creating soft landings, as its achievement is complex and unforgiving. The main policy instrument to combat inflation are adjustments in the cash rate but inflation is affected by countless factors outside of central banks control including fiscal policy, micro and macro-economic conditions, exchange rates, consumer sentiment, climate conditions, and so on. Nevertheless, central banks still hold a powerful responsibility to ensure economic stability and the soft landing remains the benchmark of effective monetary policy when responding to high inflation.

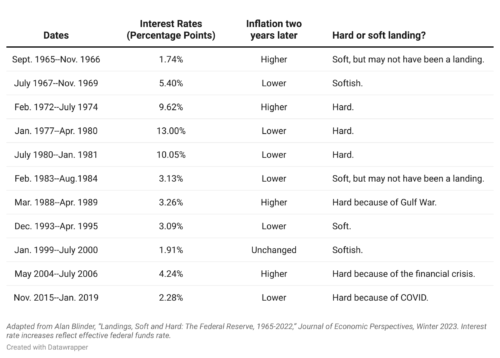

Looking at previous successful soft landings illustrates how central banks, in particular the Fed, have been able to contain excessive inflation without significant economic harm.

Source: The Brookings Institution

The December 1993 – April 1995 economic cooling cemented then-Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan into legend by producing what is regarded as the only perfect soft landing in US history. Inflation was stable at 2.8%, as the economy recovered from the inflationary highs of the 1990-91 recession. However, fearing a return to high inflation amid strong growth and shrinking inflation, Greenspan pre-emptively began raising rates as early as Q4 1993 until Q1 1995 up 206 basis points. This kept inflation stable around 3% while unemployment remained strong reaching lows of 3.8% and GDP growth remained positive concluding the soft landing.

Additionally, Alan Greenspan pioneered the use of forward guidance to stabilise market expectations. The shift toward greater transparency was used to settle uncertainty in markets as Fed decisions were previously kept secret to the public. Publicly announcing changes in its target for the federal funds rate immediately after Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings became one of the Fed’s most valuable tools, which has since been employed by successive Fed chairs.

Looking to the present, the US economy is on a trajectory towards a soft landing, propelled by astute monetary policy measures implemented by the Fed.

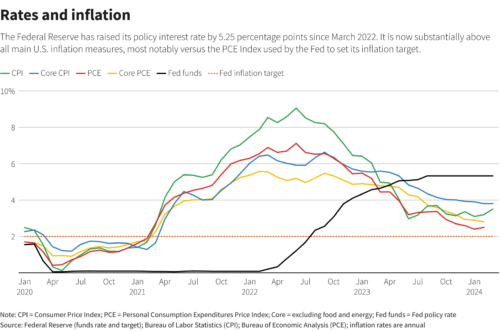

Source: Reuters

In February 2024, the inflation rate stood at 3.15%, a significant drop from its peak of 9.06% in June 2022. This achievement reflects the Fed’s successful efforts in controlling inflation and maintaining stability within a span of just one year. Moreover, with unemployment stabilising at a below-average rate of 3.7% in January, coupled with steady and low inflation, the economy has shown unexpected resilience. Despite low inflationary pressures, GDP expanded at an annualised rate of 4.9% in Q3 and 3.4% in Q4, supported by strong increases in consumer spending.

The Fed’s monetary policy measures have played a pivotal role in this success story. Beginning with modest short-term interest rate increases from 0-0.025%, the Fed gradually raised rates to a substantial 5.25-5.50% by late 2023. These strategic targets set by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) have had the effect of cooling aggregate demand and anchoring long-term inflation expectations, supporting the decline in inflation.

Comparisons to the soft landing of the 1990s reveal subtle differences. While the mid-1990s economy boasted strong household balance sheets, it grappled with higher unemployment rates compared to the current scenario. This disparity can be attributed to differences in labour market dynamics, with the current labour market exhibiting tighter conditions.

The Fed’s proactive approach in managing inflationary pressures while supporting economic growth has positioned the economy for stability and continued expansion. However, it remains to be seen whether the landing can be stuck and challenges abound.

The main challenge of a soft landing is that during the impact lag period, when the economy is already headed towards a downturn, any unexpected supply shocks would risk tipping the economy into a recession. Indeed, both the Global Financial Crisis and the Covid pandemic had plummeted the US economy into a hard landing near the end of the last two monetary policy tightening cycles. This time around, the supply shock of the war in Ukraine occurred early in the rate hikes, preventing an overreaction and unemployment was at historic lows, meaning that households were in a relatively strong fiscal position to withstand rate hikes. The Fed was undeniably lucky.

But luck is not the entire story. The Fed was able to capitalise on its luck, by responding predominantly to demand inflation, not cost inflation. By waiting until 2022 to raise rates, it allowed the post-pandemic supply shocks to recover and just as interest rate rises cooled demand, resulting in a controlled decline in inflation. Although, this delayed response could also be attributed to the belief among the Fed at the time that rising inflation was transitory, rather than the persistent pressures that eventually forced substantial rate hikes.

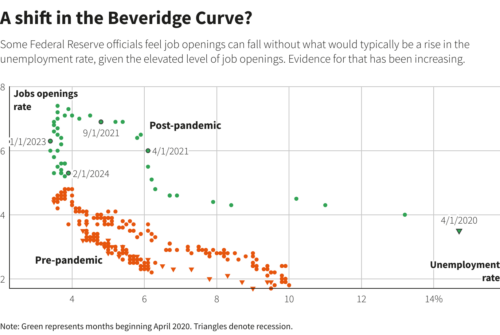

The soft landing further challenges the conventional wisdom that high interest rates will lead to a weakening in employment. The projected soft landing would set a precedent of decreasing inflation, whilst maintaining strong growth and employment. The weakening link between inflation and unemployment is supported by a strong labour market that continues to outperform expectations even amidst downward pressure on growth and employment from the Fed.

Source: Reuters

There are similar parallels to the Australian experience, a developed economy that is headed towards a moderately soft landing, and potential lessons that can be taken from the US economy. It looks possible to bring down inflation without strongly exacerbating unemployment, but the RBA may have to reduce its reliance on forward guidance as the Fed has to allow for greater flexibility and agility in policy setting.

There are factors that will be hard to replicate into the future, such as the post-pandemic consumption boom, aided by lavish government spending which helped cushion the contractionary effects of interest rate hikes. Similarly, increased wealth disparity during the pandemic allowed more high income-earners to support consumption, whilst low income-earners bear greater burden of interest rate rises. Of course, there’s also the consideration of Australian mortgage-holders being much more likely to hold variable interest loans, as opposed to the fixed interest rates seen in the US. This means that Australian borrowers are more exposed to rate hikes and its consequent cash flow effects as opposed to their US counterparts.

Nevertheless, the Fed’s experience in managing this inflation surge will likely guide monetary policy setting into the future. The soft landing proved that aggressive interest rate hikes are not the problem; rather, the issue lies in when and where. The world will watch as the Fed pauses its interest rate hikes, and when it does start to cut rates as indicated. Just as monetary policy instruments have evolved from the past, the world will learn from the Fed’s success; and when the plane of inflation takes off again in the future, our central banks will be more able to deliver those miracle soft landings.

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.