As countries around the world recognise the threat of climate change and greenhouse gasses, there has been a concerted shift towards net zero emissions and decarbonisation. This involves the process of reducing and removing net greenhouse gasses by replacing carbon-intensive energy sources with zero or low-emission alternatives (Rajah, 2021). These moves are certain to have far-reaching implications for the world economy, and in particular, for Australia. A developed economy that has thrived from its endowment of natural resources, Australia now faces a rapidly changing energy and resource landscape that will become far less reliant on its traditional exports. This presents potential challenges as well as opportunities for growth and investment. In a decarbonising world, Australia must ask: what will decarbonisation look like and what must be done to best position itself for the future?

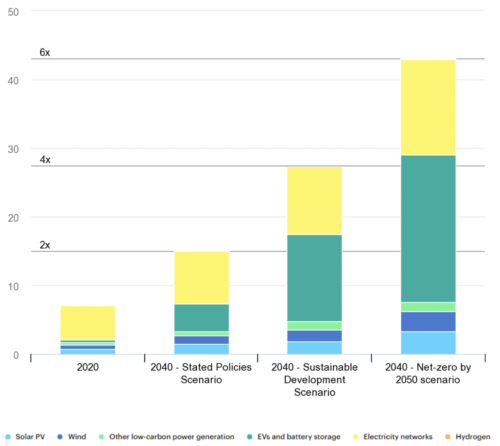

A clean energy future is soon to become reality as countries race to meet net zero and secure their place in a decarbonising world economy. The Australian government, with its aim to become a ‘renewable energy superpower’, has committed to net zero by 2050, with an interim target of a 43% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions below 2005 levels by 2030 (Readfearn, 2023). However, the country stands to face stiff competition from other developed countries with similar commitments to net zero and decarbonisation (O’Malley, 2023). These countries are joining the clean energy arms race, competing to attract massive levels of capital and investment towards energy transition, with annual investment projected to reach US$5 trillion by 2030 (IEA, 2021). Investors will be looking for renewable energy projects that particularly generate the greatest growth potential and return on investment.

The United States has become a significant investment core of the “new energy” economy with its Inflation Reduction Act and related legislation, which have provided more than US$1 trillion in incentives and support for its renewable energy industry (Hartcher, 2023). This threatens to delay and move capital projects that could support the local economy and decarbonization effort in Australia to the US or the EU due to massive subsidy and incentive schemes. In order to meet net zero by 2060, Australia will require unprecedented capital investments of AU$7-9 trillion (University of Queensland, 2023). Therefore, decarbonization is not only an environmental and moral imperative for Australia but also a strategic necessity for economic competitiveness in a clean energy economy.

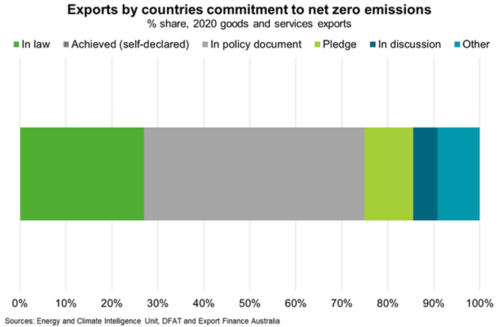

The question then becomes: what does decarbonization mean for Australia’s key exports? For decades, the Australian economy has relied on a thriving resources sector, which includes key materials such as coal, gas, and iron ore. The minerals and fuels export sector is a significant contributor to economic growth, making up 69% of all exports, and export earnings are forecast to reach a record AU$450 billion in 2022-23 (Thurtell et al., 2022). These exports represent the fundamental building blocks of the world economy, used to provide electricity and heating, as well as power industry and production. However, as economies seek to reduce their emissions, these carbon-intensive inputs will need to be phased out and replaced by less intensive resources. Australia is particularly sensitive to these changes in demand since around 85% of its exports in 2020 went to countries that have established net zero emissions targets (Export Finance Australia, 2021). This implies a reduction in demand for these exports as trading partners require fewer of Australia’s traditional natural resources during their transition to renewable alternatives. Over time, there is likely to be less reliance on fossil fuels as the world economy shifts away from “old energy” resources.

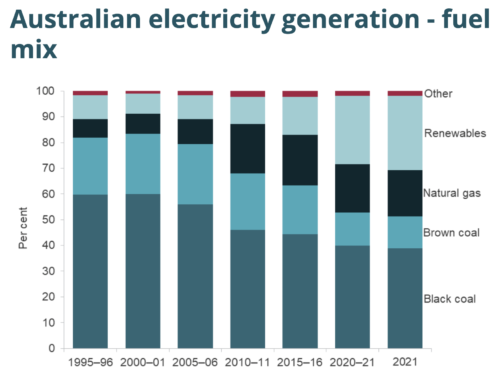

If there was any doubt about the shrinking role of fossil fuels, look no further than to what is occurring domestically. Renewable energy has experienced explosive growth in the past two decades, with renewable electricity generation quadrupling between 2000 and 2021, increasing the share of renewables in the national fuel mix from 8% to 27%, while natural gas and coal continue to trend downwards (IEA, 2023). According to forecasts, the government expects the national electricity mix to be powered by 82% renewable energy by 2030, completely displacing fossil fuel electricity generation as the dominant energy source (AOFM, 2022). In a decarbonising world where economies are no longer as reliant on natural gas and coal, the implications for Australia’s fossil fuels and traditional exports are dire.

Source: Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (2022)

A net zero world may very well spell the end of the resources boom that has fuelled Australia’s economic prosperity and lined the treasury coffers of state and federal governments in recent decades. It could leave the Australian economy in the proverbial economic dustbin as nations leverage a green energy economy that no longer requires the very things that have powered their energy supply and industrial base.

While the energy transition may seem like all doom and gloom for Australia’s three decades of prosperity, there remain many economic opportunities for “the lucky country” over the coming decades. Australia is gifted with some of the world’s best renewable resources for both wind and solar energy (Geoscience Australia, 2023), with >20% capacity factors for solar power (as seen in the lighter red segments on the map below) across the continent. These resources give the nation a key comparative advantage in energy costs globally. However, Australia currently takes limited advantage of these potentially lower energy costs, with the vast majority of electricity still being generated from coal-fired power plants. There seem to be clear opportunities for Australia’s existing energy export industry (such as large LNG producers) to transition to exporting our renewable resources instead. However, unlike gas, electricity is very hard to export due to various transportation challenges. The failed SunCable venture (funded by two of Australia’s most outspoken billionaires, McDonald Smith and Thompson, 2023) highlights the significant cost and energy losses of long-distance, subsea transmission cables, such as the one proposed between Australia and Singapore in that project. An alternative method to export electricity is through hydrogen production, in which “green hydrogen” (produced from the electrolysis of water) is liquified and shipped (much like traditional LNG exports). Despite the monumental inefficiency of hydrogen production through electrolysis, the greatest challenge to hydrogen export remains the element’s explosive characteristics (Periodic Videos, 2013). There remains no safe method to transport liquefied hydrogen through existing supply chains, which impedes its use as the future of energy exports. Therefore, more creative solutions are required to properly maximize Australia’s renewable resources.

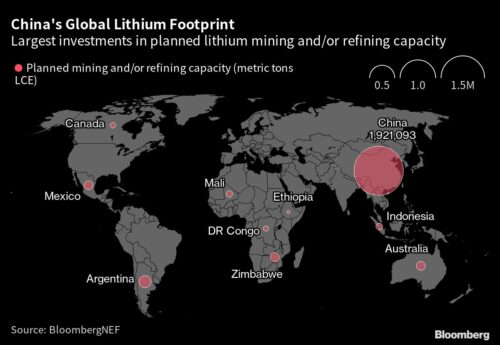

Beyond renewables, Australia also has some of the world’s largest deposits of “critical minerals” required to manufacture the goods necessary for the world’s energy transition. Lithium has captured the most public attention among these “future-facing commodities”, with the once-worthless byproduct soaring to eye-watering prices in 2022 (Trading Economics, 2023). Lithium is one of many commodities required to produce the capital goods needed for electrification, as it is a key input for batteries used for electricity storage in both electric vehicles and power grids. Australia also has vast deposits of copper, nickel, NdPr, and other rare earth metals that will only grow in importance as the energy transition beckons. The mining of these metals presents a clear opportunity for the base metal industry to transition away from mining coal and iron ore towards products with more constructive long-term demand. BHP’s buyout of Oz Minerals and Rio Tinto’s consolidation of Oyu Tolgoi represent the initial steps in the transition of Australia’s largest sector towards the commodities required to underpin the future. The structural shortfall of supply to these commodity markets provides the foundation for highly attractive long-term prices, which could underpin the next Australian mining boom.

Source: World Economic Forum, 2023

Unlike the previous mining upcycle, where Australia mined raw ore to ship to Asian steelmakers, there remains an opportunity to develop onshore value-added manufacturing that can boost the mining dividend for the Australian economy. The single-minded focus of industry on profit maximisation and lack of government intervention limited the capacity for the development of an Australian steel industry on the back of our large iron ore deposits. However, given the nascent global lithium industry, there remains a large opportunity for Australia to develop an onshore mineral processing industry for lithium and other critical minerals. This is the best way to maximize Australia’s competitive advantage in both raw resources and energy, as mineral processing is very energy-intensive. However, the cost of Australian processing facilities has been largely prohibitive thus far, with Chinese refineries being a far cheaper alternative historically. However, with deglobalization prompting much of the West to look for ex-China supply of these commodities, Australia finds itself at the precipice of a multi-trillion-dollar investment opportunity in these industries. Australian processed critical minerals would likely attract a premium to Chinese supply, as the IRA and other support for electrification in the West prioritize non-Chinese supply when offering subsidies. This could bridge the gap between the cost of production in Australia and China (as the higher cost at the Kemerton and Mt Holland (Wesfarmers, 2023) refineries can attest), but there is still a role for government support. We strongly recommend the encouragement of onshore mineral processing as a clear opportunity for the development of Australian industry that can leverage Australia’s key areas of competitive advantage through the energy transition.

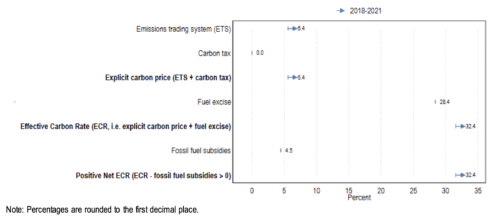

In the global push to eventually replace carbon-based energy sources with sustainable alternatives, the role of government plays a substantial role in ensuring that the domestic economy accommodates these changes. Despite being one of the biggest polluters in the world (Climate Trade Corporation, 2021), the USA has displayed exemplary efforts towards decarbonisation, largely due to its fiscal policy movements over the course of the 21st century. One of the ways in which it did this was through pricing carbon. The carbon pricing scheme consisted of the fuel excise tax, fossil fuel subsidies, and the Emissions Trading System (ETS). The tightening of these policies in the US could certainly be correlated with the growing Effective Carbon Rate (ECR) between 2018 and 2021, which is just a sum of the tax/permit/subsidy prices to give an overall carbon price as a percentage of CO2 in the air.

Source: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2022

The graph above represents the increased carbon emissions in the US. Here we can see an improvement in the net positive increase in the ECR from 31.6% in 2018 (OECD, 2022). This suggests that the carbon situation is improving in the US since a greater amount of CO2 emitted is being priced and accounted for.

The US has also directed its budget towards subsidizing greener energy to decarbonize. This has been done by relying less on fossil fuels to power the country and funding firms which sell electric vehicles in the domestic automobile industry. For instance, the Department of Energy issued a preferential loan in 2010, totalling $465 million to Elon Musk’s Tesla, which benefited greatly from reduced costs due to the tax credit policy issued by the government to consumers who purchase Tesla vehicles. By facilitating the growth of Tesla, the Federal Government allows a firm which makes sustainable alternatives to zero emissions to establish a solid market position in an industry that has otherwise been dominated by carbon-emitting cars. Encouraging products that are zero emissions and taking one closer step into decarbonizing the US.

However, has Australia been following suit? Despite having a smaller economic base and differing GDP makeup, the Labor government has made strides in both carbon pricing and subsidizing current or future alternatives. The National Reconstruction Fund (NRF) is its subsidy plan, and it is a $15 billion plan with many different industries receiving a different portion of this amount. A notable chunk of the funding is being directed towards technologies for renewables and low emissions technologies. Since some industries of renewables have a competitive advantage, putting further funds towards Research and Development will increase efficiency in their products, thus decreasing the opportunity cost of switching from high emission fossil fuels to greener alternatives.

While conducting R&D in some industries of renewables will help this, the plan also propels Australia’s potential to become a market leader in certain industries such as agriculture and resources. The plan allocates $500 million to the agricultural sector (among others like fishing) and $1 billion allocated to resources such as lithium and other non-fossil fuel commodities. Both subsidy amounts to the aforementioned sectors are aimed at encouraging value addition to their respective products. The action of subsidizing should provide economic benefit and eventual decarbonization in the long run. However, there is one major flaw in the short run, and it is that the government may have to scale back funding to other projects.

An example of this is the recent cuts imposed on the NDIS by the Labor Government. It can be implied from this information that the Labor government could be redistributing some of these funds into growing the NRF scheme. The magnitude of the effects this might have on the 580,000 participants in the NDIS is uncertain. In a not so ideal future, this may result in many disabled people and their dependents experiencing financial hardship. Therefore, while the role of the government in decarbonizing Australia is imperative to accelerating this process, it should sustain a balance such that the social consequences experienced by stakeholders in other government programs are minimized.

With increasing pressure to transform the global outlook on unsustainable commodities, decarbonising Australia is absolutely necessary for future economic growth. This can be achieved by value-adding to Australia’s abundant resources of ‘critical minerals’ required for green energy production and encouraging reliance on sustainable energy sources. The role of government will be key in this transition as it continues to tighten regulations on fossil fuel industries and foster the growth of green energy industries. With time, a successful shift in Australia’s economy towards decarbonisation could be a major factor in changing Australia’s economic position on the world stage. This then begs the question: what does a decarbonised Australia look like? It looks like an economic powerhouse represented by a competitive green energy industry, valuable export portfolio, and a brighter, economically sustainable future for the Australian people.

Australian Labor Party (n.d), National Reconstruction Fund, Labor https://www.alp.org.au/policies/national_reconstruction_fund

Australian government climate change commitments, policies and programs. Australian Office of Financial Management (2022, November). https://www.aofm.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-11-28/Aust%20Govt%20CC%20Actions%20Update%20November%202022_1.pdf

Australian Government Department of Industry, Science and Resources, (2022), National Reconstruction Fund: diversifying and transforming Australia’s industry and economy, Australian Government Department of Industry, Science and Resources https://www.industry.gov.au/news/national-reconstruction-fund-diversifying-and-transforming-australias-industry-and-economy

Australia-net zero emissions by 2050 would Alter Export Profile. Export Finance Australia. (2021). https://www.exportfinance.gov.au/resources/world-risk-developments/2021/november/australia-net-zero-emissions-by-2050-would-alter-export-profile/

CLIMATE TRADE CORP (2021), Which countries are the world’s biggest carbon polluters?, CLIMATE TRADE, https://climatetrade.com/which-countries-are-the-worlds-biggest-carbon-polluters/

Divine, J. (2023), How Much Would $10,000 Invested in Tesla Stock at IPO Be Worth Today?, U.S.News https://money.usnews.com/investing/articles/if-invested-tesla-stock-ipo-worth-today

Fernholz, T. (2023), Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Tesla get far more government money than NPR, QUARTZ https://qz.com/elon-musks-spacex-and-tesla-get-far-more-government-mon-1850332884

Hartcher, P. (2023, May 6). The US is stealing Australia’s “core”. Gym Chalmers needs the energy to STOP IT. The Age. https://www.theage.com.au/politics/federal/the-us-is-stealing-australia-s-core-gym-chalmers-needs-the-energy-to-stop-it-20230504-p5d5lc.html

Iea. (2023, April). Executive summary – Australia 2023 – analysis. IEA. https://www.iea.org/reports/australia-2023/executive-summary

OECD (2022), Pricing Greenhouse Gas Emissions I COUNTRY NOTES, OECD https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/carbon-pricing-united-states.pdf

O’Malley, N. (2023, March 1). Historic risk and opportunity in the new Clean Energy “Arms Race.” The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/environment/climate-change/historic-risk-and-opportunity-in-the-new-clean-energy-arms-race-20230301-p5cofx.html

Pathway to critical and formidable goal of net-zero emissions by 2050 is narrow but brings huge benefits, according to IEA Special Report – News. IEA. (2021, May 8). https://www.iea.org/news/pathway-to-critical-and-formidable-goal-of-net-zero-emissions-by-2050-is-narrow-but-brings-huge-benefits

Probyn A. and Worthington B. (2023), NDIS-funded disability services set for an overhaul as government seeks to slow forecasted growth. ABC News https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-05-10/ndis-eligibility-disability-services-bill-shorten/102326822

Rajah, R. (2021, February 15). Australia’s place in a decarbonising world economy. Lowy Institute. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/australia-s-place-decarbonising-world-economy

Readfearn, G. (2023, April 22). Labor promises to “grab this opportunity” to become renewable energy superpower. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/apr/22/labor-promises-to-grab-this-opportunity-to-become-renewable-energy-superpower

Thurtell, D. (Ed.). (2022, October 4). Resources and Energy Quarterly: September 2022. Department of Industry, Science and Resources. https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/resources-and-energy-quarterly-september-2022

University of Queensland. (2023, April 19). Charting Australia’s path to net zero. https://stories.uq.edu.au/news/2023/charting-australias-path-to-net-zero/index.html

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.