Overworking, although easily understood (working more hours than you should) and perhaps considered avoidable on first thought, has steadily grown as a source of workplace unhappiness and illness/death for workers, according to the WHO in 2021. This increase in overworking rates is not exclusive to countries where excessive dedication to one’s employer is the norm, such as Japan, a common example. As a result of widespread adoption of remote working, induced by the pandemic of 2020, overworking has become an even more prescient issue, with around 45% of workers logging more hours at work than previous years in 2020. Throughout this article, we will explore the contributing factors and effects of overworking, with an analysis into Japan’s infamous culture of overworking, and an overview of Australian overworking statistics and what it means for the future of the average Australian worker.

With a pandemic-induced rise in remote working, and inflationary pressures pushing workers towards undertaking multiple jobs at once, overworking is an issue which resonates globally today. A 2020 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that the average working day of workers across Europe, America and the Middle East had increased by 48 minutes. The negative impacts of overworking are both physical and mental. Namely, longer hours may cause reductions in sleep, exercise and poor dietary habits. In addition, compared to the standard 35-40 hours a week, WHO found working 55 hours or more a week increases the risk of stroke by 35% and the risk of a heart disease-related death by 17%.

While the very act of overworking has these direct impacts on workers and their families, the culture of overworking also propagates additional problems. In particular, a 2018 Expedia report showed that Japanese workers used, on average, only half of their annual leave, with 58% citing “feeling guilty” as the primary reason. Workers have noted that in Japan, “there is a culture where you would be evaluated higher if you are not taking days off” and “people think taking days off is a bad thing”. Although overworking was once necessitated by the rapid expansion of the Japanese economy, it is now a societal norm that workers feel peer-pressured into abiding by, and guilty for not. The subtle psychological effects of a work culture underpinned by guilt rather than passion manifests in alarming health and well-being statistics which highlight the worrying scale of this issue. Flexible work, open communication and job shares are some of the solutions which have been proposed to address this global health crisis from the ground-level within large organisations. However, further initiatives and research at a broader governmental level are needed, especially as society and the way individual’s work continues to develop and change rapidly.

In some cultures, the concept of overworking may seem foreign; who would voluntarily choose to work too much at the expense of their physical and mental health? In others, this concept is embedded into the very fabric of society. Perhaps the best example of this is Japan, specifically, post-World War II Japan. From the 1950s to the late 1990s, Japan experienced an economic boom, fuelled by the hard–working salarymen that resembled “shock battalions” from its warring days. However, to fuel this success, many workers in Japan had to endure overtime, usually without pay. The results of this dedication were both positive and tangible as Japan transformed from a third-world economy to an economic powerhouse, but as research continues to emerge, this extreme culture of overworking isn’t reaping nearly as positive outcomes for the contemporary Japanese labour force.

Despite a stagnating economy, Japanese workers still have one of the highest overworking rates in the world: 6th in 2021. This trend may stem from a lack of systemic change in Japanese corporate culture – specifically, the “Wa” concept: harmony through conformity. Perhaps as a result of this preference for a “harmonious society” over a more economically efficient alternative, overworking is still commonplace. As previously illustrated, overworking places individuals at risk of premature death, whether through physical illness such as heart attacks and stroke or the bleak reality of worsened mental health. Unfortunately, Japan still suffers from a large number of deaths due to overworking and karoshi culture is still very much engrained in Japanese society. Whilst there have been many attempts to curb karoshi; such as the “Premium Friday” event where workers can leave in the afternoon on Fridays, many employers and employees ignore such events or policies and continue to complete overtime at their work, exacerbating the issue further.

Here in Australia, overworking culture is slightly different. Partly due to significant migration flows post WWII and beyond, particularly in larger cities, Australia’s own workplace and overworking culture is a melting pot of attitudes from around the world.

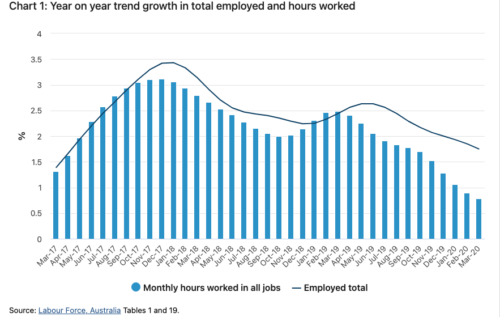

Australia’s culture of hard work can be observed quantitatively through the 25.4% of men and 10.9% of women who worked more than 45 hours per week in March 2020, with 7.6% of men and 2.6% of women working more than 60 hours per week. Nevertheless, each of these figures are lower than March 2019, indicating a movement towards working less, albeit one that may be distorted by the effects of the pandemic. Similarly to Japan, overworking still has negative impacts for Australia – at best resulting in declining productivity, and at worst endangering lives, with 70% of surgeons in public hospitals working unsafe hours.

Australia has a strong regulatory environment, which minimises the presence of poor conditions and unpaid overtime, although these still certainly exist. As the four day work week and notions of a ‘right to disconnect’ gain prominence in Europe, similar norms will likely diffuse to Australia over time – as the expectations of workers and firms gradually equalise across borders.

Therefore, while Australia has an overworking culture, it pales in comparison with Japan’s, and shows signs of developing towards a healthier and more thoughtful balance.

Overall, overworking is harmful to both productivity and personal well-being, resulting in worse physical and mental health outcomes with long term implications for the economy. While particularly prevalent and culturally ingrained in post war Japan, this issue can be seen manifesting in Australia and around the world. Although global trends indicate positive movements away from overworking, Japan’s experience shows that efforts to curb cultural norms can be difficult to implement and require significant amounts of time to take effect. Regardless of the global future of overworking, its devastating consequences make it a prevalent issue, and show that simply working more doesn’t work for everyone.

Images sourced from:

https://www.ft.com/__origami/service/image/v2/images/raw/http%3A%2F%2Fprod-upp-image-read.ft.com%2Facf5dcc8-0445-11ea-a984-fbbacad9e7dd?source=next-opengraph&fit=scale-down&width=900

https://hbr.org/2022/05/resisting-the-pressure-to-overwork

The CAINZ Digest is published by CAINZ, a student society affiliated with the Faculty of Business at the University of Melbourne. Opinions published are not necessarily those of the publishers, printers or editors. CAINZ and the University of Melbourne do not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of information contained in the publication.